Hunger and Satiety Hormones: How Your Body Regulates Appetite

Explanation of hormones and signals that regulate eating behavior and fullness

The Appetite Regulation System

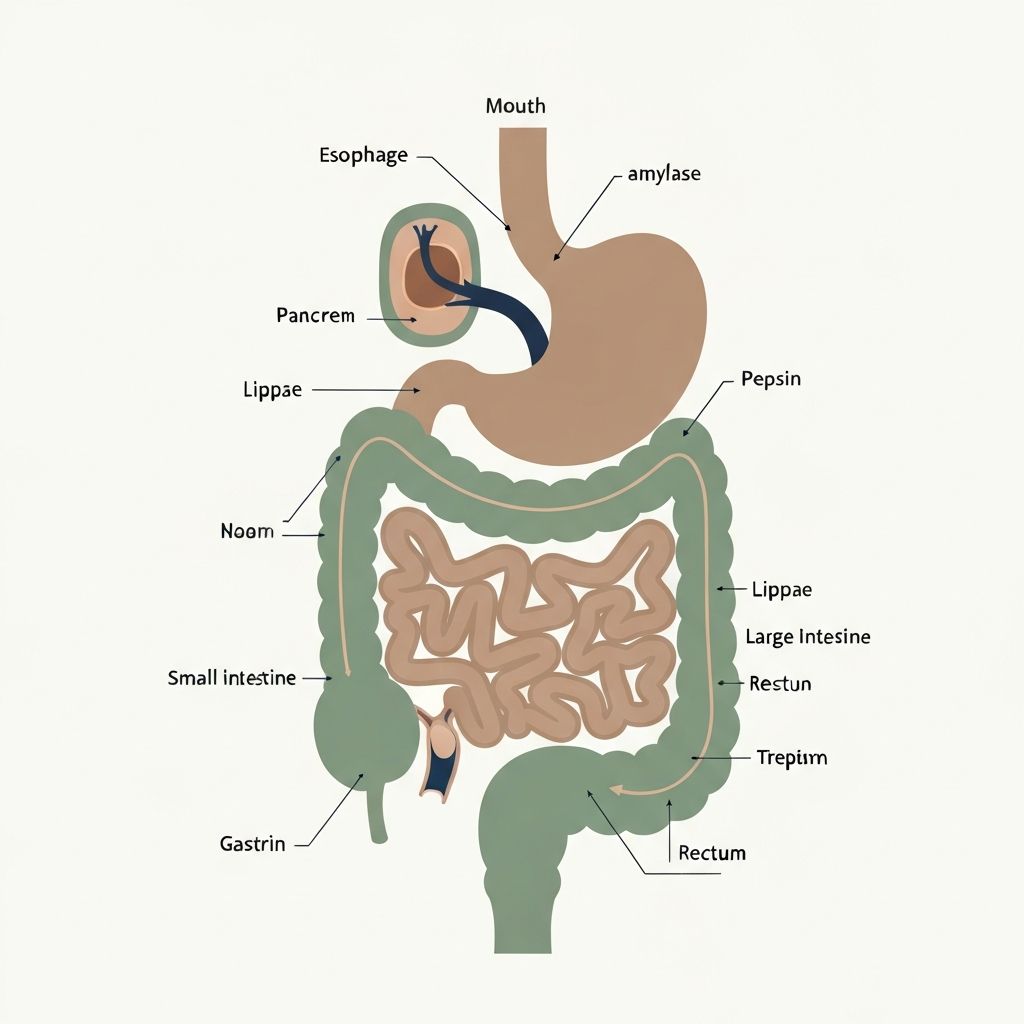

Eating behavior is not simply a matter of willpower or discipline. Instead, your body maintains sophisticated biological systems that signal hunger, fullness, and nutrient needs. These systems involve hormones, neural signals, and other mechanisms that communicate between the digestive system, brain, and metabolic systems.

Understanding appetite regulation helps explain why maintaining weight is physiologically complex and why different people experience hunger differently in similar situations.

Key Hormones in Appetite Control

Ghrelin: The Hunger Hormone

Produced primarily in the stomach, ghrelin increases before meals and signals the brain that energy is needed. Levels rise when food intake is low and fall after eating. Ghrelin is sometimes called the "hunger hormone" because of its appetite-stimulating effects. Interestingly, ghrelin levels can be conditioned by meal timing—your body may produce ghrelin in anticipation of habitual meal times.

Leptin: The Satiety Hormone

Produced by fat tissue, leptin signals to the brain about energy stores and available fat reserves. When functioning optimally, adequate leptin signals the brain that energy stores are sufficient, reducing hunger. However, in obesity, leptin resistance can develop where the brain doesn't respond normally to leptin signals, despite adequate or elevated levels.

Peptide YY (PYY)

Released from the intestines after eating, PYY signals satiety and reduces hunger. Levels increase in proportion to calorie intake, helping the body sense when sufficient energy has been consumed.

Cholecystokinin (CCK)

Released from the intestine in response to fat and protein, CCK triggers feelings of fullness and reduces food intake during a meal. It's involved in short-term satiety signaling.

Insulin

Released after eating in response to rising blood glucose, insulin not only manages glucose but also signals energy availability to the brain. Chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes can involve insulin resistance, where cells don't respond appropriately to insulin signals.

GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1)

Produced in the intestines in response to food intake, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying, increases satiety, and influences glucose metabolism. Interest in GLP-1 has increased substantially in recent years due to its multiple metabolic effects.

Neural Signals and the Brain

Beyond hormones, neural signals from the digestive system to the brain provide moment-to-moment feedback during eating. The vagus nerve carries signals about stomach stretching (fullness), nutrient sensing, and other factors.

The hypothalamus, a region of the brain, integrates these hormonal and neural signals to regulate hunger, satiety, and metabolic rate. The process is not simple signal-response but involves complex integration of multiple inputs.

Psychological and sensory factors—taste, smell, visual appearance, social context—also significantly influence eating behavior, interacting with hormonal systems.

Factors Affecting Appetite Hormones

Sleep Quality and Duration

Sleep deprivation increases ghrelin and decreases leptin, promoting hunger. Chronic poor sleep is associated with difficulty regulating appetite and weight gain in observational research.

Stress and Cortisol

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can influence appetite signaling and promote preference for calorie-dense foods. Stress-related eating patterns vary among individuals but appear influenced by hormonal changes.

Physical Activity

Regular movement influences appetite hormones and sensitivity to satiety signals, generally supporting more stable appetite regulation.

Meal Composition

Different macronutrients stimulate different satiety hormones. Protein and fiber are particularly potent satiety signals, while rapidly absorbed carbohydrates without fiber may not trigger satiety as effectively.

Meal Timing and Frequency

Individual responses to meal timing vary. Some people maintain more stable appetite with regular meals; others find irregular eating patterns work better. The pattern that supports stable hunger and satiety signals may differ among people.

Individual Variation

Important individual differences exist in baseline hormone levels, sensitivity to hormonal signals, and how various factors influence appetite hormones. Genetic factors, prior dieting history, metabolic health status, and other factors all contribute to individual differences in appetite regulation.

This explains why blanket dietary advice about meal frequency or food choices doesn't work equally for everyone. What maintains stable appetite and satiety for one person may not work the same way for another.